The Rise in Excess Deaths II

- Nicholas Qua

- Apr 3, 2023

- 24 min read

by Nicholas Qua

Introduction

Released in December 2022, I wrote an article titled The Rise in Excess Deaths, exploring and highlighting the alarming rise in excess deaths across several countries. I recommend referring to that article, as it will offer helpful and essential context to the added information in this article. The data presented directly from Government statistics (Canada, United Kingdom, USA, Australia, Scotland, European Union) and other valuable sources (Society of Actuaries, Center for Disease Control (CDC), The White House, The World Health Organization (WHO), etc) in part I is only a tiny glimpse into the complicated topic of excess deaths. Reporting methods, causes of death, what constitutes a COVID-19 death, etc., can vary from country to country.

Still, measuring is an extremely valuable tool for observing global mortality rates. When there are substantial hikes in death numbers, it is a cause for concern. Of course, during a pandemic, excess deaths are expected. Most deaths in most countries from 2020-2021 and early 2022 were from COVID-19. What is beginning to raise alarms is the considerable amount of excess deaths excluding COVID-19 in several countries starting in 2022. As seen in America, the United Kingdom, and Australia, non-COVID-19 deaths like heart disease, heart-related issues, diabetes, cancers, etc., outweighed COVID-19 deaths in 2022. As the WHO will show, COVID-19 deaths worldwide have declined since August 2022.

What are some potential causes of these alarming rates of non-COVID-19 deaths worldwide? This article will offer as an analysis and exploration of some reasons for the continued rise in excess deaths. Again, excess death is an extremely complicated topic. It must be explored cautiously and must include stats, facts, and opinions from multiple sources and various ‘experts.’

Some Updated Statistics: Canada & America

I wrote the previous article in late November 2022, so the numbers were not yet reported. Before analyzing the rise in excess deaths, an update (as brief as it may be) on the statistics is necessary. As of February 2023, Statistics Canada does not have updated death/excess death statistics for November 2022-January 2023 (at the time of writing this). Statistics Canada estimates there were about 18,329 excess deaths from January 2022-October 2022 in Canada. Important to note that the data set used by Statistics Canada is not fully completed for the entire year of 2022, and there are several provinces with no data for multiple weeks. That is why 18,329 excess deaths are an estimated number. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) COVID-19 dashboard shows about 15,576 confirmed COVID-19 deaths in Canada from January 2022-October. Despite the potentially underreported estimated excess deaths of 18,329 in Canada for January 2022-October 2022, COVID-19 deaths seem to make up most of them.

In November 2022, the CDC reported that America had 8.8-13.3% excess deaths (Figure 1). In December 2022, the percentage of excess deaths was 12.3-15.2%, up until mid-January, where it was about 8.8% (Figure 1). It is important to note that the CDC states that the deaths are underreported.

Figure 1: CDC

In November 2022, excess deaths excluding COVID-19 was around 6% (Figure 2). The percentage of non-COVID-19 deaths would slowly increase to 11.9% in the week of December 31, 2022 (Figure 2). Again, according to the CDC, deaths after December 2022 are underreported. Both Figure 1 and Figure 2 still need updated statistics for February 2023 and most of January 2023. Nonetheless, in 2022 and leading into 2023, non-COVID-19 excess deaths are concerning.

Figure 2: CDC

Europe

EuroStat reports that excess mortality rates declined from July to November 2022 before climbing in December 2022, but varied significantly between countries (Figure 3). Spain (36.8%) and Cyprus (31.3%) had the highest rates in July, while Latvia (-0.3%) and Lithuania (0.9%) had the lowest. By November, high rates were observed in Cyprus (27.7%), Germany (24.0%), and Finland (22.7%). Romania (-4.8%) and Bulgaria (-0.9%) consistently had the lowest rates. In December 2022, Germany (37.3%) had the highest rate, while Austria (27.4%), Slovenia (25.9%), Ireland (25.4%), France (24.5%), Czechia (23.2%), the Netherlands (22.7%), Estonia (22.6%), Denmark (22.4%), Finland (21.1%), and Lithuania (20.6%) were other countries with concerning rates over 20%.

Figure 3: EuroStat (Dec 2021-Dec 2022)

According to WHO’s COVID-19 Dashboard, the most COVID-19 deaths in Europe for 2022 was 27,114 during the week of February 7, 2022 (Figure 12). During this week, Our World in Data shows that the excess deaths in Europe for the week of February 6, 2022 is low in some countries and moderately high in others compared to previous weeks in 2020-2022 (Figure 3.1). WHO’s COVID-19 Dashboard highlights that in Europe, COVID-19 deaths would decline and remain low in mid-February 2022-February 2023 (Figure 12). Despite lower European COVID-19 deaths in 2022 (Figure 12), excess death rates in Europe remained high for the year (Figure 3).

When excess deaths in Europe began to rise in December 2022 (Figure 3), COVID-19 deaths remained low compared to 2020 and 2021 (Figure 12). Figure 3.2 shows the excess deaths in Europe for the week of December 25, 2022. Again, despite low COVID-19 deaths, excess deaths remain high compared to previous weeks in 2020-2021 (Figure 3.2). Eurostat shows that in Europe (excluding Russia and Belarus), there were 5,281,042 recorded deaths in 2022. WHO’s COVID-19 Dashboard shows about 451,216 confirmed COVID-19 deaths in Europe in 2022.

Figure 3.1: Our World in Data

Figure 3.2: Our World in Data

EuroMOMO offers data on excess deaths by age group in Europe from 2020-2023 (Figure 3.3). What is concerning from EuroMOMO is excess deaths for Europeans aged 0-14 and 15-44 in the latter part of December 2022 (Figure 3.3). These two age groups (0-14 & 15-44) did not see any substantial excess deaths for 2020-2021 (Figure 3.3). As we know, COVID-19 has a more profound effect on the elderly population. The concern is that despite the low amounts of European COVID-19 deaths in the latter part of 2022 (Figure 12), excess deaths for all age groups in Europe climbed in 2022.

Figure 3.3: EuroMOMO

The United Kingdom Office for National Statistics reports that the percentage of excess deaths in England and Whales for November 2022 was 9.4%, 13.5% in December 2022, and 11.7% in January 2023 (Figure 4). United Kingdom Office for National Statistics states that in both England and Wales, there was a significant increase in mortality rates in January 2023 compared to January 2022. The UK Office for Health Improvement & Disparities recorded 157,265 total deaths from November 2022-January 2023, with 17,121 of those deaths exceeding the expected amount (Figure 5). Of the 157,265 total deaths in the UK from November 2022-Janaury 2023, 6,561 mentioned COVID-19 on the death certificate (Figure 5), about 4.7% of total deaths.

Figure 4: United Kingdom Office for National Statistics (Note: ASMR=Age-standardised mortality rates)

As I mentioned in part I, a considerable amount of excess deaths for England and Whales in 2022 leading up to mid-October 2022 was from heart-related issues, cancers, and diabetes. Since October 2022, those deaths have remained the leading cause (Figure 6). From October 2022-January 2023, cardiovascular diseases (7,720 excess deaths), Acute Respiratory infections (6,566 excess deaths), diabetes (2,239 excess deaths), and other heart-related issues had high excess death numbers (Figure 6).

Figure 6: UK Office for Health Improvement & Disparities (Oct 31, 2022-Jan 27, 2023)

Similarly to Europe, excess deaths amongst the age groups of 0-24 and 25-49 were concerningly high in 2022 in the UK (Figure 5.1). Again, as shown by UK Office for Health Improvement & Disparities, most excess deaths for the ages 0-24 and 25-49 were not due to COVID-19.

Figure 5.1: UK Office for Health Improvement & Disparities (Jan 2022-Jan 2023)

Australia

Australia in 2022 saw similar high rates of excess deaths. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, By September 30th, 2022, there were 144,650 registered deaths, 16.0% higher than the baseline average, representing an additional 19,986 deaths. From January to September 2022, a total of 8,160 COVID-19 deaths were certified by doctors. In 2022, COVID-19 deaths accounted for about 5.6% of all deaths. Deaths attributed to dementia, including Alzheimer's disease, were 3.1% higher than the baseline average, and for the year (2022) up to September, they were 16.3% above the baseline average. Deaths due to diabetes were 12.1% above the baseline average in September, and for the year up to September, they were 19.2% higher than the average. Additionally, the number of deaths due to cancer was 4.2% higher than the baseline average in September.

Figure 5.2 shows excess deaths in Australia from 2016-2023. The week of January 17, 2023, was reportedly Australia’s worst week for excess deaths in 2016-2023, with 3,413 observed deaths. Similarly to most regions covered in this article, a significant portion of the observed deaths was not from COVID-19. Of the 3,413 deaths, about 2,917 were not from COVID-19 (Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2: The Australian Bureau of Statistics

Asia, Africa, and South America

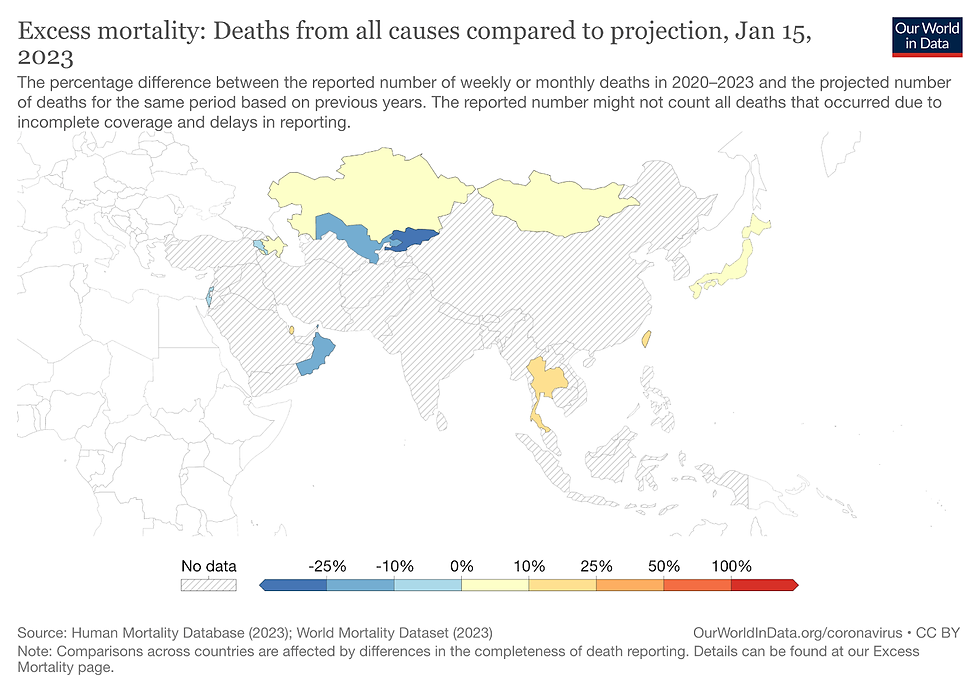

There are not a lot of statistics on excess deaths in Asia, Africa, and South America. Our World in Data offers some excess death statistics for a few countries in Asia (Figure 7), Africa (Figure 8), and South America (Figure 9). It is important to note that Figures 7,8, and 9 show the percentage difference of excess deaths from all causes in January 2023 compared to the number of deaths reported in weekly or monthly intervals between 2020-2023. Overall, Africa, Asia, and South America experienced expected high excess deaths during the pandemic (2020-2022). However, in the latter part of 2022, excess deaths in Africa, Asia, and South America began to (reportedly) decline month by month.

Figure 7: Our World in Data (Asia)

Figure 8: Our World in Data (Africa; only Egypt, South Africa)

Figure 9: Our World in Data (South America; December 2022)

Japan

According to Japan's Excess and Exiguous Deaths Dashboard, Japan saw low excess deaths in 2020-2021 (Figure 11). Excess deaths began to rise at the beginning of 2022, with highs of 13.7-19.8% or 4226-5800 excess deaths in the week of February 27, 2022 (Figure 11). According to Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, there were 1542 COVID-19 deaths in the week of February 27, 2022 (Figure 12). Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare data also shows 31,259 confirmed COVID-19 deaths from January 2022-November 2022. The Excess and Exiguous Deaths Dashboard in Japan indicates about 55,097 excess deaths in Japan between January 2022-November 2022 (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Excess and Exiguous Deaths Dashboard in Japan (Jan 2020-Nov 2022)

Figure 12: Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Feb 2022-Feb 2023)

COVID-19 in 2022

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) COVID-19 Dashboard has tracked COVID-19 cases and deaths worldwide since 2020. Figure 10 highlights the weekly confirmed COVID-19 deaths since early 2020-February 2023 in Africa, the Americas, Europe, South East Asia, the Western Pacific, and Eastern Mediterranean. As the WHO suggests, COVID-19 cases have steadily declined worldwide in the 2nd half of 2022 (except for Western Pacific). It is important to note that in the WHO’s dashboard, the America’s includes both North and South America, which might explain the higher number of COVID-19 deaths compared to the rest of the world. The WHO’s COVID-19 Dashboard also shows that COVID-19 deaths have been relatively low (reportedly) worldwide since April 2022 (Figure 10), despite the high rates of excess mortality in several countries.

Figure 10: WHO COVID-19 Dashboard

Of course, the data presented is not entirely concrete and faces many issues, such as delays or lack of reporting. Nonetheless, excess deaths were still high worldwide in 2022 and leading into 2023, despite most of them not being a direct cause of COVID-19. What are some other potential reasons for the high rates of excess deaths? Of course, I must mention that the few possible reasons for excess deaths I explore are not concrete for all countries experiencing excess deaths. Some explanations and causes might be more of a factor in one country compared to another.

COVID-19 Related Complications?

There are multiple articles and resources available authored by the CDC, Harvard Health Publishing, John Hopkins, Lopez-Leon et al. (2021), National Institute of Health, Higgens et al. (2020), Monash University (Australia), WHO, etc, discussing ‘long COVID’ or the potential issues brought on by COVID-19. Some symptoms proceeding COVID-19 infection may include fatigue, shortness of breath, cognitive problems, muscle pain, chest pain/irregular heartbeats, heart inflammation/damage, kidney pain, and reproductive issues. It is important to note that in all of the resources listed above, non of them list or discuss cases of severe hospitalization or possible death. Higgens et al. (2020) highlight the potentially serious effects of long-term COVID-19 such as pulmonary, cardiovascular, hematologic, renal, central nervous system, and gastrointestinal problems.

Not included in all of the resources above is the vaccination status of the individuals experiencing ‘long COVID’ symptoms. An article by Wang et al. (2022) found that compared to the control group (vaccinated individuals), unvaccinated individuals who survived COVID-19 were at an increased risk of experiencing cardiovascular complications such as cerebrovascular events, arrhythmia, inflammatory or ischemic heart disease, and thromboembolic disorders. Furthermore, unvaccinated COVID-19 survivors faced a significantly reduced chance of survival in all cardiovascular outcomes following infection.

In a separate article by Tuvali et al. (2022), the authors found no evidence of post-COVID-19 infection with either myocarditis or pericarditis in the cohort of unvaccinated adults in the study. Adult patients recovering from COVID-19 infection did not observe a higher incidence of pericarditis or myocarditis. Nonetheless, COVID-19 related complications and potential ‘long COVID’ might be associated with the heavy influence co-morbidities, and other underlying conditions have on the severity of COVID-19 (De-Giorgio et al., 2021, theconversation.com 2020, Edler et al., 2020, UNICEF 2021, StatsCanada 2020).

COVID-19 Lockdowns & Policies?

During the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide, most countries (mainly Western Europe & North America) entered some form of lockdown (See; BBC News, 2020). On the other hand, Sweden would not enter into any form of ‘lockdown’ during the entirety of the pandemic, which was largely viewed as controversial at the time (See; CBC News 2022, theconversation 2022, nypost 2022, FEE stories 2022). Despite the early controversial stance and high excess deaths in 2020, Sweden’s no-lockdown strategy was a success. Sweden’s total excess deaths during the first two years of the pandemic were among the lowest in Europe (Figure 13). Sweden also had one of the lowest COVID-19 mortality rates throughout the pandemic.

Figure 13: Our World in Data

Kerpen et al. (2022) recently published a study in America that assessed states based on COVID-19 outcomes, considering the number of deaths, economic impact, and effect on education. According to the article’s ‘report card,’ the bottom ten states primarily had strict pandemic lockdowns and delayed school reopenings. Herby et al. (2022) concluded that COVID-19 lockdowns in the spring of 2020 had little to no effect on COVID-19 mortality in Europe and America. TheGuardian (2022) highlights that lockdowns during the pandemic caused delays in cancer diagnosis and treatment delays. Approximately 1 million cancer diagnoses were missed across Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic, as Professor Mark Lawler of Queen’s University Belfast states: “Additionally, we saw a chilling effect on cancer research, with laboratories shut down and clinical trials delayed or canceled in the first pandemic wave. We are concerned that Europe is heading towards a cancer epidemic in the next decade if cancer health systems and cancer research are not urgently prioritized.”

The DailyMail (2022) discusses how COVID-19 lockdowns and measures (social distancing/face masks) suppressed the spread of germs crucial for building a robust immune system, especially in children. Levels of common cold viruses hit their highest level ever among under-18s in August 2021. In December 2021, 60% of children in wards with respiratory illnesses were infected with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). In the week of September 18, 2022, all emergency department visits for toddlers (4.7%) were for breathing difficulties across the US — a record high. The nypost (2022) shows how COVID-19 lockdowns had a profoundly negative effect on children's immune systems.

Putro et al. (2023) examines the delays in surgeries and treatments for individuals during lockdowns. This study “found a longer delay in surgical treatment from diagnosis of up to 12.7 weeks during the full lockdown than in light and moderate restrictions with mean of 2.4 and 5.5 weeks respectively.” Furthermore, theconversation (2022) highlights how COVID-19 restrictions doubled people’s odds of experiencing mental health symptoms. In other words, those who experienced lockdowns (in the studies) were twice as likely to experience mental ill health than those who did not.

Health Care Complications?

According to Badone (2021), the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada saw over 80% of deaths occur in long-term care homes, with Ontario and Quebec being hit particularly hard. Reports from long-term care homes in Ontario during this time revealed severe shortages of Personal Support Workers (PSWs) and Registered Nurses (RNs), leading to poor conditions for patients. Similar issues occurred during the second wave in Ontario in late 2020 and early 2021, with many long-term care residents contracting COVID-19 and receiving inadequate care. The long-term care sector in Ontario is considered to be in a humanitarian crisis.

Fellow Multipolar Marauder journalist Rvaha Afaan released an article in October 2022 discussing Canada's emergency room/health service crisis. As Afaan states in his article, in the summer of 2022, some Canadian ERs faced potential 44 hour wait times and a 33-hour wait time average in August 2022. 884 patients (on average) needed a hospital bed daily in August, about 17 hospitals closed 86 times over the 2022 Canadian summer, and about 1780 hours of care were lost. Journalist Afaan released a separate article in March 2023 on Ontario’s surgery backlog.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) alludes to similar healthcare service issues in America. For the USDHHS, it is crucial to urgently tackle the burnout crisis among healthcare workers nationwide. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers, such as physicians, nurses, community and public health workers, and nurse aides, have been confronted with systemic issues in the healthcare system, resulting in burnout levels reaching a crisis point. The pandemic has only intensified this burnout. The CDC also highlights the concerning health care staffing shortages in the country.

The WHO outlines the massive backlogs and disruptions in European health care caused by COVID-19. Similarly, theGuardian highlights the health care issue in Europe. In France, there were more doctors in 2012 compared to the time of the article (December 2022). Over 6 million individuals, including 600,000 with chronic illnesses, lack a regular general practitioner, and 30% of the population has inadequate access to healthcare services. In Germany, the number of vacant positions in the care sector reached 35,000 last year, representing a 40% increase from a decade ago. A report released this summer predicted that by 2035, more than one-third of all healthcare jobs could remain unfilled. Finland is experiencing unprecedented hospital overcrowding due to a severe shortage of nurses and will require 200,000 new healthcare and social care workers by 2030. In Spain, the health ministry reported in May that more than 700,000 individuals were awaiting surgical procedures. Moreover, in Madrid, 5,000 frontline general practitioners and pediatricians have been on strike for nearly a month, protesting years of underfunding and overwork.

TheGuardian released a separate article on the health care crisis in England. The article claims that up to 500 individuals may lose their lives every week due to emergency care delays. England's statistics from November 2022 show that 37,837 patients had to wait for more than 12 hours to receive a decision on admission to a hospital department. This represents a significant rise of almost 355% compared to the previous November, where an estimated 10,646 patients experienced a similar wait time. The House of Lords (2023) in England released an article in January 2023 outlining the healthcare crisis, deeming it an emergency. In their action plan (pg 7), they list a few solutions to the emergency, such as recognizing the crisis as an emergency, delivering care on time and at the right location, unlocking the gridlock, understanding the problem, addressing unmet needs, and new models for emergency health services.

Overall Health?

The Government of Canada released a statement in February 2023 about obesity: “In Canada, almost two in three adults and one in three children and youth are overweight or living with obesity.” According to StatsCanada reports, in 2018 approximately 7.3 million Canadian adults aged 18+, which accounts for 26.8% of the population, reported being obese based on their height and weight. Furthermore, 36.3% or 9.9 million adults were categorized as overweight, resulting in a total of 63.1% of the population at increased risk of health problems due to excess weight. This is an increase from 2015, where 61.9% of Canadian adults aged 18+ were overweight or obese.

The CDC reports that the percentage of obesity in the US between 2017 and March 2020 was 41.9%. Over the period from 1999-2000 to March 2020, there was an increase in obesity prevalence from 30.5% to 41.9%. In the same time frame, the percentage of severe obesity also rose from 4.7% to 9.2%. EuroStat provides data regarding the percentage of individuals who are overweight or obese in the European Union and Norway, Serbia, and Turkey. The incidence of weight issues and obesity has steadily risen in many EU member states, with an estimated 52.7% of adults aged 18 and above being overweight in 2019. According to Britain’s National Health Service (NHS), in 2021, 26% of adults in England were obese. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (IHW) reports that around 12.5 million Australian adults, two-thirds of those aged 18 and over, were classified as overweight or obese in 2017-18. Of this number, 36% were overweight but not obese, while 31% were classified as obese.

It is important to note that Britain’s NHS, StatsCanada, CDC, EuroStat, and Australia’s IHW, measure obesity using the Body Mass Index (BMI). The BMI is a tool used to measure body fat in adult men and women by taking into account their height and weight. The BMI is not the best for measuring obesity/overweight/overall health in general. Of course, obesity is an issue that is more complicated than just body mass divided by height. Nonetheless, it is still a helpful measurement when considering the entire population. Of course, it is well known that obesity can lead to a plethora of health complications and several dieted-related diseases like heart disease, type-2 diabetes, and cancer. WebMD states obesity makes it more likely to have conditions like heart disease and stroke, high blood pressure, insulin resistance and diabetes, cancers, gallbladder disease and gallstones, and osteoarthritis, to name a few.

Along with obesity, micronutrient deficiencies are common worldwide, even in ‘developed’ countries. Micronutrients are the vitamins and minerals required by the body in trace amounts. Despite the small quantities needed, they play a crucial role in maintaining overall health, and their deficiency can result in severe and potentially fatal conditions. According to the WHO, iron, vitamin A, and iodine deficiencies are prevalent worldwide, especially among children and expectant mothers. The WHO states: “Micronutrient deficiencies can cause visible and dangerous health conditions, but they can also lead to less clinically notable reductions in energy level, mental clarity, and overall capacity. This can lead to reduced educational outcomes, reduced work productivity, and increased risk from other diseases and health conditions.”

The Government of Canada states the percentage of adults aged 19 and above that had inadequate intakes of vitamin B12, and vitamin C was from 10% to 35% below the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR). Vitamin A, vitamin D, magnesium, and calcium were among the nutrients with the highest prevalence of inadequate intakes. Over 35% of adults consumed vitamin A in amounts below the EAR, and this prevalence was higher than 40% in most adult age and sex groups. Similarly, more than a third of Canadian adults had magnesium intakes below the EAR, and the prevalence of inadequate intakes exceeded 40% in half of the adult age and sex groups.

Oregon University released an article in 2019 highlighting that in America, 94.3% of individuals do not meet the daily requirement for vitamin D, 88.5% for vitamin E, 52.2% for magnesium, 44.1% for calcium, 43.0% for vitamin A, and 38.9% for vitamin C, potassium, 91.7% for choline, and 66.9% for vitamin K. In addition, more than 97% of the population exceeded the age-specific Upper Limit (UL) for daily sodium intake, indicating excessive sodium intake. Nutri-Facts states that a significant proportion of certain population groups in Europe fail to meet nutrient recommendations, with at least half falling short. Specifically, low intakes of thiamine in Italian women, vitamin B6 in women from multiple countries, and vitamin C in Scandinavian men and male smokers have been reported. Furthermore, vitamin D and E intake are insufficient for most individuals in Northern, Western, and Southern Europe.

COVID-19 Vaccines?

There is no lack of government organizations, websites, and other institutions like the WHO or the CDC reaffirming the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines. I say this as I am aware that I might receive backlash for questioning the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines. Nevertheless, there is evidence that some COVID-19 vaccines have not been entirely safe. Oster et al. (2022) report that from 354 100 845 mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines during the study period, there were 1991 reports of myocarditis. Lv et al. (2021) state that as of January 8, 2021, there were 55 reported deaths associated with COVID-19 vaccination, resulting in a mortality rate of 8.2 per million population. Of these fatalities, 37 occurred among individuals residing in long-term care facilities, with a mortality rate of 53.4 per million population. The most commonly reported underlying health conditions associated with these deaths were hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and heart failure.

Chiu et al. (2023) conducted a study on Taiwanese high schoolers and the effects of the BNT162b2 (Pfizer) vaccine and ESG parameter changes (changes in the electrical activity of the heart). Of the 7934 eligible Taiwanese students, 4928 (62.1%) completed the pre- and post-vaccine questionnaire. The authors found “the incidence of cardiac-related symptoms after the second dose BNT162b2 vaccine was 17.1%, which was significantly higher than that of the first dose (5.7%).” The individual items of cardiac-related symptoms such as chest pain, palpitations, and dizziness or syncope were significantly higher after the second dose of BNT162b2 vaccine.” Furthermore, pediatric cardiologists compared the ECGs taken before and after vaccination, and they determined that 51 students (1.03%) had significant changes in their ECGs following vaccination.

Another study by Kwan et al. (2022) looked at the association between COVID-19 vaccination and new POTS-related (postural orthostatic tachycardic syndrome) diagnoses by comparing the odds of diagnosis in the 90 days before the first vaccine exposure with the 90 days following the vaccine exposure. The study included 284,592 patients with an average age of 52. The majority of vaccinations received were Pfizer-BioNTech (62%), followed by Moderna (31%), and Johnson & Johnson/Janssen (6.9%). A small number (<0.1%) received other vaccines, such as AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1-S), Novavax (NVX-CoV2373), and Sinovac (CoronaVac). After vaccination, the five conditions with the highest odds of new diagnoses were myocarditis, dysautonomia, POTS, mast cell activation syndrome, and urinary tract infection (UTI).

The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) is a system that receives reports of adverse events that occur following vaccination. Anyone can submit reports, including healthcare providers, vaccine manufacturers, and the public. It is important to note that VAERS reports alone cannot be used to determine whether a vaccine caused or contributed to an adverse event or illness. VAERS reports may also contain incomplete, inaccurate, coincidental, or unverifiable information. Additionally, reports to VAERS can be biased. While VAERS is vital for monitoring vaccine safety, the data collected should be interpreted cautiously. Nevertheless, MedAlerts uses VAERS monthly updated data to make tables of the data. As of March 3, 2023, there were 1,506,723 reported cases of adverse events following COVID-19 injection. Some of the more notable reported outcomes of adverse events were: deaths (34,455 reports), permanent disability (63,756 reports), prolonged hospitalized visits (2,259 reports), birth defects (1,235 reports), and life-threatening (36,588 reports).

The UK government also releases (about monthly) updated death numbers by vaccination status. Using the data from the UK government between January and May 2022, TheExpose created graphs and charts demonstrating deaths by vaccination status. Figure 14 includes monthly age-standardized mortality rates by vaccination status. It shows that for all age groups, monthly mortality rates were higher in the one-three dose cohorts compared to the unvaccinated (Figure 14). Using TheExpose graphs here, I am not arguing that COVID-19 vaccination is directly related to all deaths recorded in the UK’s stats. What I want to highlight is how in 2022 COVID-19 deaths in the UK were relatively low and made up only a small percentage of deaths in 2022. Yet, from January-May 2022, individuals with 1-3 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine were more likely to die compared to unvaccinated (Figure 14).

Figure 14: TheExpose (using data from UK government)

Conclusion

As stated multiple times, excess deaths is a highly complicated topic. There are so many external factors at play when discussing this complex topic. Nonetheless, what I tried to convey was that beginning in 2022 and following into 2023, excess deaths have still been concerningly high. Of course, excess deaths from 2020-2021 can safely be attributed to COVID-19. However, reported COVID-19 deaths have drastically decreased in most countries worldwide. Despite the declining COVID-19 deaths, excess deaths remain high. I attempted to investigate some contributing factors to the non-COVID-19 excess deaths, like COVID-19-related issues, initial COVID-19 policies, health care/service complications, overall health, and COVID-19 vaccines. These factors are only a glimpse into why the world has continued seeing excess deaths.

References

Afaan, R. (2022, October). ER Crisis: Unacceptable Closures and Wait Times. Multipolar Marauder. https://multipolar-marauder.github.io/website/index.html

Afaan, R. (2023). Ontario’s Surgery Backlog. Multipolar Marauder. https://multipolarmarauder.wixsite.com/website/post/ontario-s-surgery-backlog-are-private-for-profit-centers-the-answer

Andrews, L. (2022, October 6). More toddlers are being hospitalized with colds, CDC reports says. Mail Online. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-11287779/Record-numbers-toddlers-hospitalized-colds-immunity-weakened-restrictions.html

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022, December 22). Provisional Mortality Statistics, Jan - September 2022 | Australian Bureau of Statistics. Www.abs.gov.au. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/causes-death/provisional-mortality-statistics/latest-release#mortality-by-selected-causes-of-death

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2023). Measuring Australia’s excess mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic (doctor-certified deaths) | Australian Bureau of Statistics. Www.abs.gov.au. https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/measuring-australias-excess-mortality-during-covid-19-pandemic-doctor-certified-deaths

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022, July 7). Overweight and Obesity. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/overweight-and-obesity

Badone, E. (2021). From Cruddiness to Catastrophe: COVID-19 and Long-term Care in Ontario. Medical Anthropology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2021.1927023

Canada, P. H. A. of. (2023, March 4). Message from the Minister of Health – World Obesity Day 2023. Www.canada.ca. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/news/2023/03/message-from-the-minister-of-health--world-obesity-day-2023.html

CBC News. (2022, February 26). Sweden’s no-lockdown COVID strategy was broadly correct, commission suggests. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/sweden-report-coronavirus-1.6364154

CDC. (2021a, February 11). Adult Obesity Facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html

CDC. (2021b, September 16). Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a, February 11). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/mitigating-staff-shortages.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b, August 12). Excess Deaths Associated with COVID-19. Www.cdc.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/excess_deaths.htm

Chiu, S.-N., Chen, Y.-S., Hsu, C.-C., Hua, Y.-C., Tseng, W.-C., Lu, C.-W., Lin, M.-T., Chen, C.-A., Wu, M.-H., Chen, Y.-T., Chien, T.-C. H., Tseng, C.-L., & Wang, J.-K. (2023). Changes of ECG parameters after BNT162b2 vaccine in the senior high school students. European Journal of Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04786-0

De-Giorgio, F., Grassi, V. M., Bergamin, E., Cina, A., Del Nonno, F., Colombo, D., Nardacci, R., Falasca, L., Conte, C., d’Aloja, E., Damiani, G., & Vetrugno, G. (2021). Dying “from” or “with” COVID-19 during the Pandemic: Medico-Legal Issues According to a Population Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8851. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168851

Drake, V. (2019, April 13). Micronutrient Inadequacies in the US Population: an Overview. Linus Pauling Institute. https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/micronutrient-inadequacies/overview

Dunford, D., Dale, B., Stylianou, N., Lowther, E., Ahmed, M., & de la Torre Arenas, I. (2020, April 6). Coronavirus: A visual guide to the world in lockdown. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52103747

Edler, C., Schröder, A. S., Aepfelbacher, M., Fitzek, A., Heinemann, A., Heinrich, F., Klein, A., Langenwalder, F., Lütgehetmann, M., Meißner, K., Püschel, K., Schädler, J., Steurer, S., Mushumba, H., & Sperhake, J.-P. (2020). Dying with SARS-CoV-2 infection—an autopsy study of the first consecutive 80 cases in Hamburg, Germany. International Journal of Legal Medicine, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-020-02317-w

EuroMOMO. (2023). Graphs and maps from EUROMOMO. EUROMOMO. https://www.euromomo.eu/graphs-and-maps/#

European Statistics. (2023). Weekly death statistics. Ec.europa.eu. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Weekly_death_statistics#Data_sources

EuroStat. (2021). Overweight and obesity - BMI statistics - Statistics Explained. Ec.europa.eu. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Overweight_and_obesity_-_BMI_statistics

EuroStat. (2023). Excess mortality. Europa.eu. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/DEMO_MEXRT__custom_309801/bookmark/line?lang=en&bookmarkId=26981184-4241-4855-b18e-8647fc8c0dd2

Frans, E. (2022, August 12). Did Sweden’s controversial COVID strategy pay off? In many ways it did – but it let the elderly down. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/did-swedens-controversial-covid-strategy-pay-off-in-many-ways-it-did-but-it-let-the-elderly-down-188338

Government of Canada. (2020, November 16). COVID-19 death comorbidities in Canada. Www150.Statcan.gc.ca. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00087-eng.htm

Government of Canada. (2021, May 14). Adjusted number of deaths, expected number of deaths and estimates of excess mortality, by week. Www150.Statcan.gc.ca. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310078401

Harvard Health Publishing. (2020, October 8). The hidden long-term cognitive effects of COVID-19. Harvard Health Blog. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/the-hidden-long-term-cognitive-effects-of-covid-2020100821133

Health Canada. (2010, January 27). Do Canadian Adults Meet Their Nutrient Requirements Through Food Intake Alone? Www.canada.ca. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-nutrition-surveillance/health-nutrition-surveys/canadian-community-health-survey-cchs/canadian-adults-meet-their-nutrient-requirements-through-food-intake-alone-health-canada-2012.html#a33

Hempton, C., & Trabsky, M. (2020, September 9). “Died from” or “died with” COVID-19? We need a transparent approach to counting coronavirus deaths. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/died-from-or-died-with-covid-19-we-need-a-transparent-approach-to-counting-coronavirus-deaths-145438

Herby, J., Jonung, L., & Hanke, S. (2022). KandasamyA LITERATURE REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS OF THE EFFECTS OF LOCKDOWNS ONCOVID-19 MORTALITY. John Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise.

Higgins, V., Sohaei, D., Diamandis, E. P., & Prassas, I. (2020). COVID-19: from an acute to chronic disease? Potential long-term health consequences. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences, 58(5), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2020.1860895

House of Lords. (2023). Emergency healthcare: a national emergency.

Japan Excess Deaths. (2023). Excess and Exiguous Deaths Dashboard in Japan. 日本の超過および過少死亡数ダッシュボード. https://exdeaths-japan.org/en/graph/weekly/

Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2023, February). Visualizing the data: information on COVID-19 infections. Covid19.Mhlw.go.jp. https://covid19.mhlw.go.jp/en/

Johns Hopkins Medicine. (2021, April 1). COVID “Long Haulers”: Long-Term Effects of COVID-19. Www.hopkinsmedicine.org. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus/covid-long-haulers-long-term-effects-of-covid19

Karantzas, G. (2022, April 12). Lockdowns doubled your risk of mental health symptoms. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/lockdowns-doubled-your-risk-of-mental-health-symptoms-180953

Kerpen, P., Moore, S., & Mulligan, C. (2022, April). A Final Report Card on the States’ Response to COVID-19. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Kwan, A. C., Ebinger, J. E., Wei, J., Le, C. N., Oft, J. R., Zabner, R., Teodorescu, D., Botting, P. G., Navarrette, J., Ouyang, D., Driver, M., Claggett, B., Weber, B. N., Chen, P.-S., & Cheng, S. (2022). Apparent risks of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome diagnoses after COVID-19 vaccination and SARS-Cov-2 Infection. Nature Cardiovascular Research, 1(12), 1187–1194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44161-022-00177-8

Lopez-Leon, S., Wegman-Ostrosky, T., Perelman, C., Sepulveda, R., Rebolledo, P. A., Cuapio, A., & Villapol, S. (2021). More than 50 Long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. MedRxiv: The Preprint Server for Health Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.27.21250617

Lv, G., Yuan, J., Xiong, X., & Li, M. (2021). Mortality Rate and Characteristics of Deaths Following COVID-19 Vaccination. Frontiers in Medicine, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.670370

Miltimore, J. (2022, March 24). Sweden—Once Mocked for Its COVID Strategy—Now Has One of the Lowest COVID Mortality Rates in Europe | Jon Miltimore. Fee.org. https://fee.org/articles/sweden-once-mocked-for-its-covid-strategy-now-has-one-of-the-lowest-covid-mortality-rates-in-europe/

Monash University. (2022, September). Long-term effects of COVID-19 revealed in important Australian study. Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences. https://www.monash.edu/medicine/news/latest/2021-articles/long-term-effects-of-covid-19-revealed-in-important-australian-study

National Health Service. (2022). Overweight and obesity in adults. NDRS. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2021/overweight-and-obesity-in-adults

National Institutes of Health. (2022, December). Long COVID Information and Resources | National Institutes of Health. NIH COVID-19 Research. https://covid19.nih.gov/covid-19-topics/long-covid#what-we-know-about-long-covid-1

National Vaccine Information Center. (2023). Search Results from the VAERS Database. Www.medalerts.org. https://www.medalerts.org/vaersdb/findfield.php?TABLE=ON&GROUP1=CAT&EVENTS=ON&VAX=COVID19

Nutri-Facts. (2017). Micronutrient Deficiencies Throughout the World. @Nutri-Facts. https://www.nutri-facts.org/en_US/news/articles/-micronutrient-deficiencies-throughout-the-world.html

nypost. (2022a, May 6). Sweden saw fewer COVID-19 deaths than majority of Europe. Nypost. https://nypost.com/2022/05/06/sweden-saw-fewer-covid-19-deaths-than-majority-of-europe/

nypost. (2022b, June 14). Kids’ immune systems weakened after COVID lockdowns. Nypost.com. https://nypost.com/2022/06/14/kids-immune-systems-weakened-after-covid-lockdowns/

ons.gov.uk. (2023). Deaths by vaccination status, England - Office for National Statistics. Www.ons.gov.uk. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/datasets/deathsbyvaccinationstatusengland/deathsoccurringbetween1april2021and31december2022

Oster, M. E., Shay, D. K., Su, J. R., Gee, J., Creech, C. B., Broder, K. R., Edwards, K., Soslow, J. H., Dendy, J. M., Schlaudecker, E., Lang, S. M., Barnett, E. D., Ruberg, F. L., Smith, M. J., Campbell, M. J., Lopes, R. D., Sperling, L. S., Baumblatt, J. A., Thompson, D. L., & Marquez, P. L. (2022). Myocarditis Cases Reported After mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccination in the US From December 2020 to August 2021. JAMA, 327(4), 331. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.24110

Our World in Data. (2023, February). Excess mortality: Deaths from all causes compared to projection. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/excess-mortality-p-scores-projected-baseline?tab=map&time=2023-01-22&country=MEX~RUS~ZAF

Putro, Y. A. P., Magetsari, R., Mahyudin, F., Basuki, M. H., Saraswati, P. A., & Huwaidi, A. F. (2023). Impact of the COVID-19 on the surgical management of bone and soft tissue sarcoma: A systematic review. Journal of Orthopaedics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2023.02.013

Statistics Canada. (2019, June 25). Overweight and obese adults, 2018. Statcan.gc.ca; Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-625-x/2019001/article/00005-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2023). Provisional weekly estimates of the number of deaths, expected number of deaths and excess mortality. Www150.Statcan.gc.ca. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310078401&cubeTimeFrame.startDaily=2022-01-01&cubeTimeFrame.endDaily=2022-12-03&referencePeriods=20220101%2C20221203

The Exposé. (2022, August 9). UK Government confirms COVID Vaccines are deadly as they reveal Mortality Rates per 100k are lowest among the Unvaccinated in all Age Groups. The Expose. https://expose-news.com/2022/08/09/mortality-rates-lowest-among-unvacinated/

TheGuardian. (2022a, November 15). Europe faces “cancer epidemic” after estimated 1m cases missed during Covid. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/nov/15/europe-faces-cancer-epidemic-after-estimated-1m-cases-missed-during-covid

TheGuardian. (2022b, December 14). “A ticking time bomb”: healthcare under threat across western Europe. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/dec/14/a-ticking-time-bomb-healthcare-under-threat-across-western-europe

TheGuardian. (2023, January 1). A&E delays causing up to 500 deaths a week, says senior medic. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jan/01/up-to-500-deaths-a-week-due-to-ae-delays-says-senior-medic

Tuvali, O., Tshori, S., Derazne, E., Hannuna, R. R., Afek, A., Haberman, D., Sella, G., & George, J. (2022). The Incidence of Myocarditis and Pericarditis in Post COVID-19 Unvaccinated Patients—A Large Population-Based Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(8), 2219. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11082219

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022, May 23). New Surgeon General Advisory Sounds Alarm on Health Worker Burnout and Resignation. HHS.gov. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2022/05/23/new-surgeon-general-advisory-sounds-alarm-on-health-worker-burnout-and-resignation.html

UNICEF. (2021). Co-morbidities and COVID-19. Www.unicef.org. https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.unicef.org/armenia/en/stories/co-morbidities-and-covid-19&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1678721374993555&usg=AOvVaw2vh3fPbIBXHTJzOZ98qQRy

United Kingdom Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. (2023, February). Excess Mortality in England. App.powerbi.com. https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiYmUwNmFhMjYtNGZhYS00NDk2LWFlMTAtOTg0OGNhNmFiNGM0IiwidCI6ImVlNGUxNDk5LTRhMzUtNGIyZS1hZDQ3LTVmM2NmOWRlODY2NiIsImMiOjh9

United Kingdom Office for National Statistics. (2023, February). Deaths registered weekly in England and Wales, provisional - Office for National Statistics. Www.ons.gov.uk. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsregisteredweeklyinenglandandwalesprovisional/weekending3february2023#related-links

VAERS. (2023, March). VAERS - Data. Vaers.hhs.gov. https://vaers.hhs.gov/data.html

Wang, W., Wang, C.-Y., Wang, S.-I., & Wei, J. C.-C. (2022). Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in COVID-19 survivors among non-vaccinated population: A retrospective cohort study from the TriNetX US collaborative networks. EClinicalMedicine, 53, 101619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101619

WebMD. (2002, April 12). Health Risks Linked to Obesity. WebMD; WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/diet/obesity/obesity-health-risks

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Micronutrients. Www.who.int. https://www.who.int/health-topics/micronutrients#tab=tab_1

World Health Organization. (2022a, July). COVID-19 has caused major disruptions and backlogs in health care, new WHO study finds. Www.who.int. https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/20-07-2022-covid-19-has-caused-major-disruptions-and-backlogs-in-health-care--new-who-study-finds

World Health Organization. (2022b, September). At least 17 million people in the WHO European Region experienced long COVID in the first two years of the pandemic; millions may have to live with it for years to come. Www.who.int. https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/13-09-2022-at-least-17-million-people-in-the-who-european-region-experienced-long-covid-in-the-first-two-years-of-the-pandemic--millions-may-have-to-live-with-it-for-years-to-come

World Health Organization. (2023). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Covid19.Who.int. https://covid19.who.int/?mapFilter=deaths

Comments